Latest national statistics show decrease in cancer deaths, room for improvement

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) recently released its Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, showing that overall cancer mortality rates continue to decline in men, women and children in the United States from 1999-2016.

The downward trend in cancer deaths underscores advances in biomedical research and efforts being made by physicians, researchers and policy makers to diminish the damaging effects of cancer. However, the report also includes significant observations that may impact the direction of future cancer-fighting endeavors.

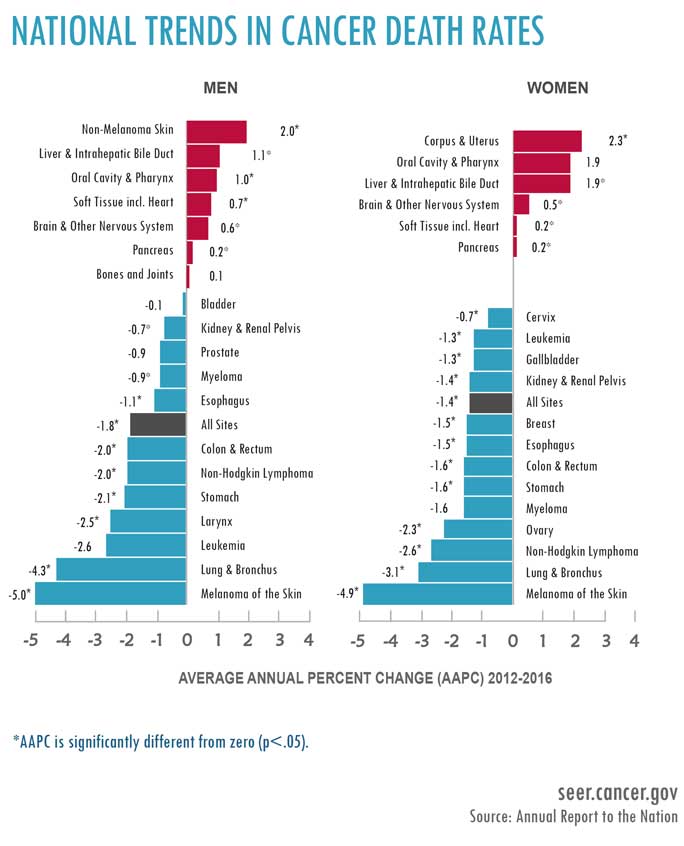

From 2012 to 2016, overall cancer mortality decreased by an average of 1.8% for men and 1.3% for children ages 0-14 years. For women, cancer-related deaths decreased by 1.4% on average from 2002 to 2016. Furthermore, 10 of the 19 most common cancers in men and 13 of the 20 most common cancers in women showed decreases in mortality.

Each year that the overall cancer death rates fall represents another step in the right direction.

These positive trends reflect a decline in the smoking rate resulting from comprehensive tobacco control and decreases in cervical cancer due to HPV vaccination. Furthermore, between 1999 and 2015, overall cancer incidence rates (new cases of cancer per 100,000 people in the United States) continued to fall among men and have remained stable among women.

Melanoma and Immunotherapy

Contributing to these optimistic results is the statistic that death rates for melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, have decreased dramatically among men, age 20-49, and women, age 20-29, between 2012 and 2016. This decline can be attributed to the introduction of immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, that are giving patients new, more effective treatment options.

At the UChicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center, Journal of Experimental Medicine that connects obesity to cancer through the immune system.

Their study found that obesity changes macrophages—white blood cells that form the first line of defense against bacteria or tumor cells—into pro-inflammatory macrophages that promote breast cancer rather than fight it. In addition to raising awareness over the risks produced by obesity, “our bottom line is to promote weight loss as a cancer prevention measure,” says Rosner.

Cancer Disparities and Age

The report included a special section about cancer among young people, which revealed some interesting findings about how cancer affects men differently than woman. For example, among people of all ages, overall cancer incidence (2011-2015) and death rates (2012-2016) were higher in men. However, when the researchers looked at just the 20-49 age group, women experienced higher cancer incidence and death rates than men.

Notably, breast cancer occurs in this age group far more than any other cancer, meaning research focused on prevention, early detection and treatment of breast cancer in younger women should be a priority.

In another interesting observation, because a substantial number of men and women in the 20-49 age group were treated early on in life for a previous in situ breast cancer or nonmalignant central nervous system tumor, frequent malignant and nonmalignant tumors that occur in this age group could be the result of long-term, late effects associated with the earlier disease or its treatment.

As such, the authors suggest that access to high-quality treatment and survivorship care is important to improve health outcomes and quality of life for younger adults. Survivorship research experts at the UChicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center are devoted to addressing the unique needs of this population through comprehensive cancer care and clinical research to better understand the challenges they face.

Progress and Promise

Each year that the overall cancer death rates fall represents another step in the right direction. Beyond this good news, the report contains many valuable lessons about cancer that can inform ongoing and future efforts. Public health measures like tobacco control and HPV vaccination can play a major role in reducing cancer rates. Breakthrough treatments like immunotherapy can change the course for some patients who previously had few options. Weight loss and healthy diet interventions can potentially stem the tide of obesity-related cancer cases.

Finally, significant differences remain in cancer cases and deaths based on gender, ethnicity and race, signaling that much more work is needed to understand why some groups are affected by cancer more severely than others.

“This report shows that it is vital we continue to support cancer research with an eye toward cancer risk and prevention, particularly with regard to young adults,” says Michelle Le Beau, PhD, Arthur and Marian Edelstein Professor of Medicine and director of the University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center. “Fighting cancer is not an easy task, but our physicians and scientists at the University of Chicago are determined to change the cancer landscape for the better.”

To learn more about what the Comprehensive Cancer Center is working on across many types of cancer, please view the UChicago Medicine is designated as a Comprehensive Cancer Center by the National Cancer Institute, the most prestigious recognition possible for a cancer institution. We have more than 200 physicians and scientists dedicated to defeating cancer.

UChicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center