This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Lloyd I. Sederer, MD: Hello. I'm Dr Lloyd Sederer, and I'm the director of Columbia Psychiatry Media. This broadcast is a collaboration between Columbia Psychiatry and Medscape. I'm here with Dr Jack Drescher, a good friend, a psychiatrist, a psychoanalyst, an author, and one of the more important people involved in the changes to how American psychiatry has perceived and regarded homosexuality. Our topic today is going to be how the perception of homosexuality in psychiatry has changed across a long period of time, and we're going to have your expertise on that. Welcome, Jack.

Jack Drescher, MD: Thank you. So nice to be here.

Stonewall Riots

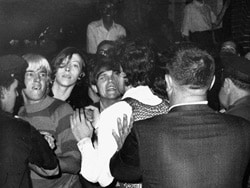

Sederer: This past June marked the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots. What was this all about? Why do we celebrate a riot?

Drescher: That is a great question. The Stonewall riots took place in New York City in Greenwich Village. At the time of the Stonewall riots, it was common practice in many cities in the United States for the police to raid gay bars. Gay bars at the time were one of the few places where gay people could meet each other for socializing, for dancing, to find partners, etc. Many of those bars were run by the Mafia, at least in New York City, and most of them used to pay our—at the time—very corrupt police department protection money not to be raided. But periodically, a raid would take place because either the bar had not paid their protection money or to set an example to other bars: "This is what happens if you don't pay protection money." They would call reporters and journalists and say, "We're going to raid this bar tonight, and we'd like you to be there so that you can take down the names and the information about the people we arrest."

Sederer: There was a shaming element to this.

Drescher: Absolutely. And not only that, but the crime for which they were usually arrested in the bar was same-sex dancing. It was illegal in New York at the time to do that.

Sederer: Those attitudes prevailed only 50 years ago.

Drescher: It was 1969. Some people attribute what happened to the fact that people were very upset because Judy Garland, who was a gay icon, had died in June of '69. I don't know if that's true. But that night, when the police came to raid the bar, the patrons of the bar fought back. And the fighting back spread throughout the Village. These 3 days of rioting in Greenwich Village mobilized and energized the national gay rights movement. There had been gay rights organizations in the United States since the 1950s, who used to call themselves "homophile" organizations. They were very polite people who would dress up in jackets and ties, and picket and get out in front of places to protest discrimination against gay people.

Sederer: This riot, in a way, catalyzed a much larger movement around the country.

Views of Homosexuality Within the Field of Psychiatry

Sederer: Let's shift to psychiatry because American psychiatry has had its views and had its diagnostic labels for people with homosexuality. American psychiatry has a checkered past here. Why is that? What was it that earned them a black mark about attitudes about homosexuality?

Drescher: The history of psychiatry and homosexuality begins in the 19th century in Europe. Most people attribute this to Richard von Krafft-Ebing, a German-Austrian psychiatrist who wrote a very famous catalog of sexual diversity called Psychopathia Sexualis. If you were in the book, it meant that there was something psychopathological about you, because that is how it worked in the 19th century. You just needed a psychiatrist to say you had an illness to have one. He wrote about homosexuality; he also wrote about transgender presentations but he called that homosexuality too. He was famous for popularizing the word "homosexuality." The word had been invented before, I think, in 1868 by a Hungarian journalist.

Sederer: This was about making homosexuality an aberration. Not only was this important in the way that it would condemn people with homosexuality, but it was a shift away from hundreds of years, millennia, of views about homosexuality as madness, badness, or possession.

Drescher: Sin. Homosexuality was a sin. The sin of sodomy. And what Krafft-Ebing and many people in psychiatry did afterwards was say, "This is not about religion. This is about science." In the language of science, many psychiatrists said, "This is what we call illness," or "This is what we call pathological or psychopathological." That became the starting point for many people.

Sederer: And it began to change. What did Freud say about homosexuality?

Drescher: Around the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, Freud wrote three essays on the theory of sexuality. He saw it as a form of developmental arrest. He said that everybody had bisexual, homosexual, and heterosexual feelings but homosexual feelings were not supposed to persist into adulthood. And the reason they did was because you had an arrest in psychosexual development. That was Freud's view, and I call it a theory of immaturity. I write that there are three basic ideas within psychiatry about homosexuality: It's normal, it's pathological, or it's a developmental arrest or immaturity. You see throughout the history of psychiatry people arguing from these three basic positions. Eventually, Freud's view did not really get taken up by his followers, particularly here in the United States. Psychiatrists in America pathologized homosexuality, and so when the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) came out in 1952, homosexuality was listed with pedophilia and what we now call paraphilias or sexual deviations.

Sederer: The first DSM made homosexuality a pathology.

Drescher: Exactly. And the same was true when DSM-II came out in 1968.

Sederer: Why, in your view, did it take American psychiatry to recognize that homosexuals are no different from anybody else and many, like yourself, are esteemed members of our community? Why did it take so long?

Culture and Activism

Drescher: That is a good question. There is a very important book by Ronald Bayer called Homosexuality in American Psychiatry: The Politics of Diagnosis, still out in print. Definitely worth a read. The book really talks about how psychiatry's views basically reflect back the views of the culture in which it lives. The culture at the time was very much [filled with] heterosexist, bourgeois, middle-class values. There was discrimination. You could be fired from your job for being a homosexual. That was the mood at the time of DSM-I and also DSM-II. Psychiatry was just reflecting back values within the larger society, even though scientific studies were beginning to emerge, starting with the Kinsey work in the 1940s that homosexuality appeared to be a normal variation of human sexuality.

Sederer: A troubling event happened in the '50s. A documentary recently was released called The Lavender Scare, and it was about Joe McCarthy's hearings about homosexuality. There was the Red Scare, and then there was the Lavender Scare. Tell us about what McCarthy was doing in the '50s.

Drescher: McCarthy's view was that the American system was being corrupted by left-wing communists under foreign influence and by homosexuals who undermined true American values. He tried to ferret out people from the government who were either Communist or interested in Communism, or people who were known to be homosexual. And that became the Lavender Scare. An irony of the Lavender Scare is that one victim of the rules that forced gay people out of their jobs was Dr Frank Kameny, an astronomer who worked for the US government.

Sederer: He was a very capable scientist, so his firing was not on the basis of competence.

Drescher: No. It was based on prejudice. He later became instrumental and an important figure in leading the movement to get the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to remove homosexuality from the DSM.

Sederer: When did that happen?

Drescher: Homosexuality was removed from the DSM-II in 1973. Energized by the Stonewall riots in 1969, gay activists disrupted the 1970 APA meeting in San Francisco. They walked into lecture rooms and grabbed the microphones.

Sederer: I'm old enough to remember.

Drescher: That is before my time; I think I was still in college in 1970. They called doctors who were showing how to use electric aversive treatments to cure homosexuality "Nazi" doctors. This disruption did get APA's attention.

Sederer: Speaking out can make a difference. People who organize and assert their views can play a role.

Drescher: Yes, activism has its role. Activism may be the only choice you have when diplomacy and polite language don't work. Prior to the changes back then, homophile movements of the 1950s and 1960s were split about whether to work with psychiatry or not. Some people said, "The illness label is okay. People shouldn't make it illegal, because we have an illness." Before we had the Americans with Disabilities Act, some people thought you should not discriminate against gay people because they have a mental disorder. But the activists and Frank Kameny and Barbara Gittings said, "No. It's the diagnosis itself which perpetuates the stereotypes and perpetuates the stigma."

Sederer: Where are we today? Where are the DSM and the ICD-11 today?

Drescher: Today, homosexuality is not a diagnosis in either the DSM-5, which came out in 2013, or in ICD-11, which came out this year. I worked on both. There used to be diagnoses like ego-dystonic homosexuality in DSM-III, which got taken out in 1987 in DSM-III-R. And ICD-10 had a diagnosis called ego-dystonic sexual orientation and a few fellow travelers along those lines, and those did not make it into the ICD-11.

Controversy Over Gay Genes

Sederer: We're getting over our prejudice as a national organization that has so much influence through the DSM, the bible of psychiatric care. Before we run out of time, I want to ask you about an article you recently wrote about gay gene studies. Why did you write that article, and what did you say?

Drescher: I was invited by Psychiatric News, APA's newspaper, to write something about a gay gene study that was about to come out. I said, "Well, what do I have to say about this?" A lot of my work, particularly with gay men in my psychiatry/psychotherapy practice, has to do with people trying to figure out why they are gay. I'd like the audience to know that today in 2019, we don't know why anybody is gay. Some people say you are born gay. Some people say you are converted gay. We don't know why people are gay. We just know that it's very difficult to change, and that for many people, it feels intrinsic to who they are.

But everybody comes in [wondering], "Why am I gay?" Gay gene theories tend to support the view that people are born gay. When people believe that you are born gay, they are less likely to feel that you should discriminate against gay people.

Sederer: But there was no finding that there are gay genes, right?

Drescher: There was no finding that there is one gay gene. Some studies were done in the '90s by Dean Hamer and his associates, saying they found a gene on the X chromosome that they thought might be a cause of homosexuality. But this study says no, there is no one gene that causes it and we still don't know what causes it. What I wrote in the article is that people will spin that each way because, in the culture wars today, whether you think homosexuality is a good thing or a bad thing has a lot to do with what you think causes it. And so for people who believe that homosexuality is okay, they think it's okay because you're born that way.

Sederer: Right. This is a good place for us to stop, because it looks like, even in the whole area of gene studies, we're discovering that there are no simple answers. Perhaps people's identity and sexuality are a complex matter of genes and environment; we just don't know.

Drescher: Exactly. And a lot of people don't like the idea of not knowing.

Sederer: And some of them come to your office curious.

Drescher: Yes. One thing you want to do in treatment is help people be comfortable with the idea of uncertainty.

Sederer: Thank you for being our guest and thank you for your wisdom on homosexuality and psychiatry, and on psychoanalysis in general.

Drescher: Thank you for having me. It's was a pleasure to be here.

Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, is a professor in the Department of Epidemiology at Columbia University in New York City, as well as the director of Columbia Psychiatry Media. He is the former Distinguished Psychiatric Advisor to the New York State Office of Mental Health. Sederer's most recent book is The Addiction Solution: Treating Our Dependence on Opioids and Other Drugs.

Jack Drescher, MD, is a clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University in New York City. He is known for his work on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

© 2019 WebMD, LLC

Cite this: The 'Checkered' History of Psychiatry's Views on Homosexuality - Medscape - Dec 03, 2019.

Comments