Dr Ruiyuan Zhang

Low to moderate alcohol consumption is associated with better cognitive function and slower cognitive decline in middle-aged and older adults, new research suggests. However, at least one expert urges caution in interpreting the findings.

Investigators at the University of Georgia College of Public Health in Athens found that consuming 10 to 14 alcoholic drinks per week had the strongest cognitive benefit.

The findings "add more weight" to the growing research identifying beneficial cognitive effects of moderate alcohol consumption, lead investigator, Ruiyuan Zhang, MD, told Medscape Medical News.

However, Zhang emphasized that nondrinkers should not take up drinking to protect brain function, as alcohol can have negative effects.

The study was published online June 29 in JAMA Network Open.

Slower Cognitive Decline

The observational study was a secondary analysis of data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative US survey of middle-aged and older adults. The survey, which began in 1992, is conducted every 2 years and collects health and economic data.

The current analysis used data from 1996 to 2008 and included information from individuals who participated in at least three surveys.

The study included 19,887 participants, mean age 61.8 years. Most (60.1%) were women and white (85.2%). Mean follow-up was 9.1 years.

Researchers measured cognitive function by assessing total word recall, mental status using tests of knowledge, language, and orientation, and vocabulary. They also calculated a total cognition score, with higher scores indicating better cognitive abilities.

For each cognitive function measure, researchers categorized participants into a consistently low trajectory group in which cognitive test scores from baseline through follow-up were consistently low or a consistently high trajectory group, where cognitive test scores from baseline through follow-up were consistently high.

Based on self-reports, investigators categorized participants as never drinkers (41.8%), former drinkers (39.5%), or current drinkers (18.7%).

For current drinkers, researchers determined the number of drinking days per week and number of drinks per day. They further categorized these participants as low to moderate drinkers or heavy drinkers.

One drink was defined as a 12-ounce bottle of beer, a 5-ounce glass of wine, or a 1.5-ounce shot of spirits, said Zhang.

Women who consumed eight or more drinks per week, and men who drank 15 or more drinks per week, were considered heavy drinkers. Other current drinkers were deemed low to moderate drinkers. Most current drinkers (85.2%) were low to moderate drinkers.

Other covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, years of education, marital status, tobacco smoking status, and body mass index.

Results showed moderate drinking was associated with relatively high cognitive test scores. After controlling for all covariates, compared with never drinkers, current low to moderate drinkers were significantly less likely to have consistently low trajectories for total cognitive score (odds ratio [OR], 0.66; 95% CI, 0.59 - 0.74), mental status (OR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.63 - 0.81), word recall (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.69 - 0.80), and vocabulary (OR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.56 - 0.74) (all P < .001).

Former drinkers also had better cognitive outcomes for all cognitive domains. Heavy drinkers had lower odds of being in the consistently low trajectory group only for the vocabulary test.

Heavy Drinking "Risky"

Because few participants were deemed to be heavy drinkers, the power to identify an association between heavy drinking and cognitive function was limited. Zhang noted, though, that heavy drinking is "risky."

"We found that after the drinking dosage passes the moderate level, the risk of low cognitive function increases very fast, which indicates that heavy drinking may harm cognitive function." Limiting alcohol consumption "is still very important," he said.

The associations of alcohol and cognitive functions differed by race/ethnicity. Low to moderate drinking was significantly associated with a lower odds of having a consistently low trajectory for all four cognitive function measures only among white participants.

A possible reason for this is that the study had so few African Americans (they made up only 14.8% of the sample), which limited the ability to identify relationships between alcohol intake and cognitive function, said Zhang.

"Another reason is that the sensitivity to alcohol may be different between white and African American subjects," he said.

There was a significant U-shaped association between weekly amounts of alcohol and the odds of being in the consistently low trajectory group for all cognitive functions. Depending on the function tested, the optimal number of weekly drinks ranged from 10 to 14.

Zhang noted that when women were examined separately, alcohol consumption had a significant U-shaped relationship only with word recall, with the optimal dosage being around 8 drinks.

U-shaped Relationship an "Important Finding"

The U-shaped relationship is "an important finding," said Zhang. "It shows that the human body may act differently to low and high doses of alcohol. Knowing why and how this happens is very important as it would help us understand how alcohol affects the function of the human body."

Sensitivity analyses among participants with no chronic diseases showed the U-shaped association was still significant for scores of total word recall and vocabulary, but not for mental status or total cognition score.

The authors note that 77.2% of participants had at least one chronic disease. They maintain that the association between alcohol consumption and cognitive function may be applicable both to healthy people and to those with a chronic disease.

The study also found that low to moderate drinkers had slower rates of cognitive decline over time for all cognition domains.

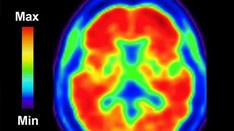

Although the mechanisms underlying the cognitive benefits of alcohol consumption are unclear, the authors believe it may be via cerebrovascular and cardiovascular pathways.

Alcohol may increase levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a key regulator of neuronal plasticity and development in the dorsal striatum, they note.

Balancing Act

However, there's also evidence that drinking, especially heavy drinking, increases the risk of hypertension, stroke, liver damage, and some cancers.

"We think the role of alcohol drinking in cognitive function may be a balance of its beneficial and harmful effects on the cardiovascular system," said Zhang.

"For the low to moderate drinker, the beneficial effects may outweigh the harmful effects on the small blood vessels in the brain. In this way, it could preserve cognition," he added.

Zheng also noted that the study focused on middle-aged and older adults.

"We can't say whether or not moderate alcohol could benefit younger people" because they may have different characteristics, he said.

The findings of other studies examining the effects of alcohol on cognitive function are mixed. While studies have identified a beneficial effect, others have uncovered no, minimal, or adverse effects.

This could be due to the use of different tests of cognitive function or different study populations, said Zhang.

A limitation of the current study was that assessment of alcohol consumption was based on self-report, which might have introduced recall bias.

In addition, because individuals tend to underestimate their alcohol consumption, heavy drinkers could be misclassified as low to moderate drinkers, and low to moderate drinkers as former drinkers.

"This may make our study underestimate the association between low to moderate drinking and cognitive function," said Zhang.

In addition, alcohol consumption tended to change with time, and this change may be associated with other factors that led to changes in cognitive function, the authors note.

Interpret With Caution

Commenting on the study for Medscape Medical News, Brent P. Forester, MD, chief, Center of Excellence in Geriatric Psychiatry, McLean Hospital, associate professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, and a member of the American Psychiatric Association Council on Geriatric Psychiatry, said he views the study with some trepidation. Forester is

"As a clinician taking care of older adults, I would be very cautious about over- interpreting the beneficial effects of alcohol before we understand the mechanism better," he said.

He noted that all of the risk factors associated with heart attack and stroke are also risk factors for Alzheimer's and cognitive decline more broadly.

"So one of the issues here is how in the world does alcohol reduce cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risks, if you know it increases the risk of hypertension and stroke, regardless of dose," he said.

With regard to the possible impact of alcohol on BDNF, Forester said, "it's an interesting idea" but the actual mechanism is still unclear.

Even with dietary studies, such as those on the Mediterranean diet that include red wine, showing cognitive benefit, Forester said he's still concerned about the adverse effects of alcohol on older people.

These can include falls and sleep disturbances in addition to cognitive issues, and these effects can increase with age.

He was somewhat surprised at the level of alcohol that the study determined was beneficial. "Essentially, what they're saying here is that for men, it's two drinks a day."

This could be "problematic" as two drinks per day can quickly become more daily drinks as individuals build tolerance.

He also pointed out that the study does not determine cause and effect, noting that it's only an association.

Forester said the study raises a number of questions, including the type of alcohol study participants consumed and whether this has any impact on cognitive benefit. He also questioned whether the mediating effects of alcohol were associated with something that wasn't measured such as socioeconomic status.

Another question, he said, is what factors in individuals' medical or psychiatric history determine whether they are more, or less, likely to benefit from low to moderate alcohol intake.

Perhaps alcohol should be recommended only for "select subpopulations" — for example, those who are healthy and have a family history of cognitive decline — but not for those with a history of substance abuse, including alcohol abuse, said Forester.

"For this population, the last thing you want to do is recommend alcohol to reduce risk of cognitive decline," he cautioned.

The study was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The investigators and Forester have reported no relevant financial disclosures.

JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e207922. Full text

For more Medscape Psychiatry news, join us on Facebook and Twitter.

Medscape Medical News © 2020 WebMD, LLC

Send comments and news tips to news@medscape.net.

Cite this: Does Moderate Drinking Slow Cognitive Decline? - Medscape - Jul 07, 2020.

Comments