Dr Anthony Cunliffe and Dr Abhijit Gill Suggest Approaches Through Which Primary Care Networks and GP Practices Can Improve Early Stage Cancer Diagnosis

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

|

As outlined by Dr Cunliffe in a previous Guidelines in Practice article, Improving cancer recognition and referral in primary care,1 primary care is the first point of contact for most people who are diagnosed with cancer.2–6 However, many under-represented populations have a higher risk of being diagnosed with cancer at a later stage, and report worse experiences of care.7–11 Therefore, primary care teams have a vital role to play in not only helping patients to receive a diagnosis at an early stage—thus improving their chances of a good outcome—but also ensuring that they have the best and most equitable experience of diagnosis as possible.

Both the Primary Care Network (PCN) Directed Enhanced Service (DES) and the associated Investment and Impact Fund (IIF) include elements intended to help primary care to create the best opportunities for early cancer diagnosis.12,13 The PCN DES has been in place for 3 years now; recently, changes have been made to the service requirements for early cancer diagnosis in the 2022–202314 specifications, and also in the 2023–202412 specifications (see Box 1).

| Box 1: PCN DES Early Cancer Diagnosis Requirements 2023–202412 |

|---|

Service Requirements

NHS England. Network Contract DES—contract specification for 2023/24—PCN requirements and entitlements. London: NHS England, 2023. Available at: www.england.nhs.uk/publication/network-contract-des-contract-specification-for-2023-24-pcn-requirements-and-entitlements Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. |

In this article, we will consider these changes and make suggestions on how primary care can best meet the requirements, with a focus on screening and referral practices. We will also offer some practical proposals for assessing the impact of any interventions made.

Screening for Cancer

Cancer screening is essential for achieving early stage diagnosis in individuals who are asymptomatic or who have not yet presented to the healthcare system,15 perhaps because they have not associated their symptoms with a potential underlying cancer. There are three national screening programmes in place for cervical,16 colorectal,17 and breast cancers.18 However, uptake of these programmes is low in many areas, and also in underserved populations including people who are from minority ethnic backgrounds, live in areas of social deprivation, or have learning disabilities.19–22

The PCN DES provides an opportunity for primary care teams—working with other members of integrated care partnerships—to improve local uptake of these programmes, and offers the possibility of targeting specific demographics most likely to benefit from evidence-based interventions. Improvements in this area can definitely have a significant, long-term impact: a 25-year-old woman potentially has 27 cancer screening opportunities ahead of her as part of these programmes. Early intervention, education, and awareness may have an impact on attendance long term.

Accessing and Using Data

Understanding local screening data is an essential part of any activity intended to improve engagement with screening programmes, and reviewing these data is an important first step in assessing the impact of an intervention or planning a future activity. Easily accessible national data are available on the Office for Health Improvement & Disparities’ Fingertips website.23 Moreover, it may be useful to contact the leads at the local Cancer Alliance, as they may be able to provide further data on the local population.24,25

Bowel Screening

The National Bowel Cancer Screening Programme is primarily aimed at individuals aged 60–74 years, although it is currently being expanded to include people from the age of 50 years by 2025.17,26 This is the newest of the three screening programmes, meaning that it is not as embedded as the others. This may in part explain why uptake in some integrated care board (ICB) areas was as low as 56.9% in 2021–2022.27

Within this screening programme, the previous faecal occult blood (FOB) test has been replaced by the more sensitive faecal immunochemical test (FIT),17,28 meaning that an individual with a positive result has approximately a 9% chance of having a colorectal cancer.29 In England in 2018, 59.8% of people diagnosed with bowel cancer who presented via screening received early stage (stage 1 or 2) diagnoses, compared with only 42.7% of people diagnosed through the 2-week-wait pathway or another form of GP referral.30 This demonstrates the strength of the screening programme, even before the change from FOB to FIT, for early stage bowel cancer diagnosis.

The Role of Primary Care

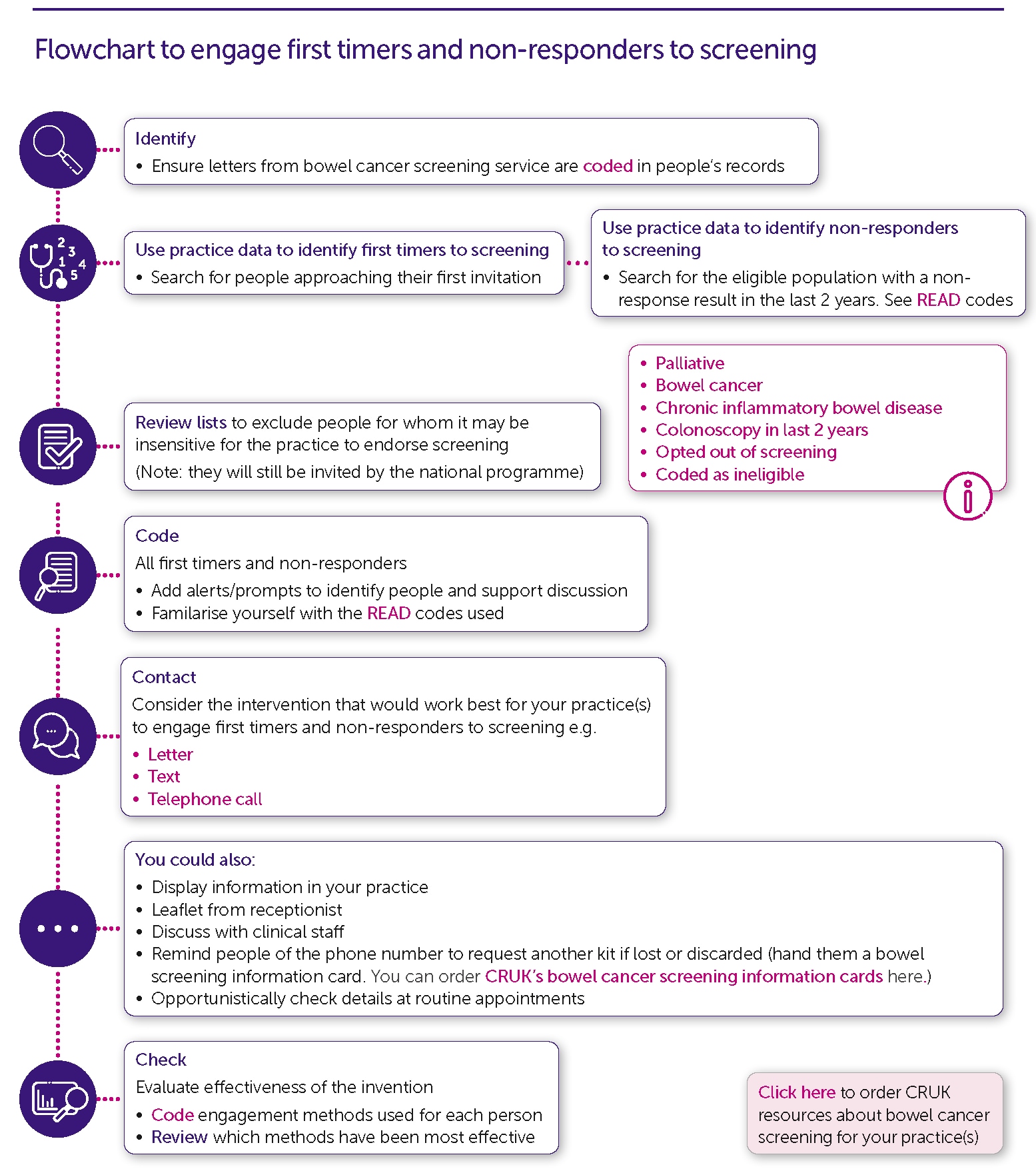

Evidence shows that primary care endorsement can significantly improve engagement with bowel screening, and there are various ways in which PCNs and primary care teams can intervene to increase uptake in their area.28,31 Various studies involving GP-endorsed letters, enhanced patient leaflets, and GP endorsement banners on standard invitations have yielded improvements in uptake ranging from 0.7–12%.28,31 Other interventions involving primary care have also been shown to increase uptake, including telephone advice, face-to-face health promotion, enhanced reminder letters, and text message reminders.28 Cancer Research UK has produced a useful flowchart on screening uptake that outlines ways to engage first timers and nonresponders (Figure 1).32

Figure 1: Flowchart to Engage First Timers and Nonresponders to Screening32

Nonresponders

Bowel cancer screening results should already be coded automatically into GP computer systems, and practices can set up alerts for when a patient does not return their FIT. Practices may be able to improve the engagement of nonresponders at this time—and potentially make them more likely to engage in future rounds of screening—by proactively reaching out to them to discuss the screening programme and ensure that they understand the benefits of screening.28,31 Some practices may instead send out reminder text messages or letters to nonresponders endorsing the programme and explaining why they feel it is important to take part.31

If a patient then decides to participate in screening, they can call the bowel cancer screening helpline on 0800 707 6060 to request a replacement kit.31 In some areas, the practice can instead email the local screening hub or call the screening helpline and request a kit on the patient’s behalf,31 which may be particularly helpful for less active or more vulnerable patients.

To address inequalities when undertaking any of these activities, it is important to consider people who may need additional support.32 This includes people who would benefit from being provided with an easy-to-read explanation of the importance of bowel screening,33 or who may need their practice team to take more robust action, such as ordering a kit on their behalf.

Some less resource-intensive options include using incidental opportunities to discuss screening and its benefits with patients, such as long-term condition reviews, flu clinics, or another situation in which a patient attends and is flagged as a nonresponder. Other examples include adding specific tabs for screening into relevant long-term condition review templates, such as the one for ‘serious mental illness’, or using a multilingual recall service for populations with a higher proportion of nonresponders. However, these interventions would likely be more suitable at the system level, so are worth discussing with a local ICB or Cancer Alliance.

Other Considerations

There are a couple of other important things to remember regarding bowel cancer screening. Firstly, practices’ own FITs, which are used as a diagnostic tool for patients with symptoms, must not be given to nonresponders for screening purposes. This is because the threshold for determining a positive result differs between the two tests (120 mcg of haemoglobin per gram of faeces for screening, as opposed to 10 mcg for symptomatic pathways in England34). Secondly, if it is not sent from the screening hub, the result of a FIT will not be acted upon by the screening programme. Relatedly, the cancer indicator for the 2023–2024 IIF concerns the ‘percentage of lower gastrointestinal [2-week-wait] cancer referrals accompanied by a [symptomatic FIT] result’, with results recorded in the 21 days leading up to referral.13 This demonstrates the importance placed on early bowel cancer identification by the NHS, with the introduction of FITs for both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

Another important consideration, which patients should be informed of, is that bowel screening can lead to the identification of polyps before they turn malignant, so can actually prevent cancer from developing as well as aiding diagnosis at an early stage.35

Cervical Screening

Cervical screening is offered every 3 years to women aged 25–49 years, and every 5 years to women aged 50–64 years.16 Four weeks before a patient’s first invitation for screening is sent out, practices receive prior notification lists, alerting them to patients who will be receiving an invitation and giving them the opportunity to manage any fully informed patients who do not want or need to be screened.36 Patients for whom there are no test results 18 weeks after their first invitation are classed as ‘overdue’, and should receive a reminder letter; if this is still the case after 32 weeks, they will be classed as a ‘nonresponder’.36 At this point, GPs should receive a notification in their clinical systems informing them that the person has not participated.36 In alignment with this process, practices or PCNs can set up text messages to be sent after the first or second invitations, encouraging those who have not been screened to book an appointment.37

Interventions to Improve Uptake

Many of the interventions for improving uptake of bowel screening are applicable to cervical screening.37 For cervical screening in particular, however, clinicians should be aware of the resources available for supporting underserved populations, such as people with learning disabilities.37,38 Two populations to pay special consideration to are transgender men and nonbinary people: when registered as ‘male’ or ‘I’ (Indeterminate), these individuals will not be automatically enrolled in the programme.37,39

Practices and PCNs can also offer training for both clinical and nonclinical staff about their role in screening programmes, either generally or with a focus on cervical cancer, and may benefit from discussing this with their local Cancer Alliance or basing their training on the information and resources provided by Cancer Research UK (CRUK), Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust, or NHS England.37,40–42

From a practical point of view, there are various things that PCNs and practices can do to ensure that there is sufficient capacity and flexibility in their offering of appointments to maximise patients’ opportunities to attend for screening. For example, to support patients to get an appointment at a time that is suitable for them, it is essential that appointments are available at different times of the day, and that there are enough sample takers available whose training is up to date.

Prostate Cancer Case Finding

Currently, there is no national screening programme for prostate cancer; screening is not currently recommended for this condition because methods such as prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing or imaging are insufficiently accurate, raising the risk of false-negative and false-positive results.43 However, the urological cancer pathway is one of those most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and many areas still have a backlog of predicted prostate cancer diagnoses.44,45 Accordingly, the PCN DES suggests that PCNs ‘develop and implement a plan to increase the proactive and opportunistic assessment of patients for a potential [prostate] cancer diagnosis in population cohorts where referral rates have not recovered to their prepandemic baseline’, using data provided by the local Cancer Alliance and informed by public health specialists.12,46 Those identified as most at risk in the DES are:46

- aged 50 years or older

- aged 45 years or older with either Black ethnicity or a family history of prostate cancer.

- are aware of their risk

- have the opportunity to discuss this with a healthcare professional

- undergo a PSA test and examination if it is appropriate and they choose to do so, in line with NICE guidance.

Breast Screening

Although breast screening is not explicitly named in the PCN DES requirements as a programme to target, the 2023–2024 version of the support pack for implementation does ‘strongly recommend that PCNs review the uptake of breast cancer programmes’.12,46 Indeed, many of the interventions that improve engagement with the other screening programmes are just as applicable to breast screening, and PCNs and practices can certainly consider activity in this area as well.

Reviewing and Improving Referral Practice

Another requirement of the PCN DES is to ‘review referral practice for suspected and recurrent cancers, and work with the PCN’s community of practice, to identify and implement specific actions to improve referral practice, particularly among people from disadvantaged areas where early diagnosis rates are lower’ (see Box 1).12 This element offers myriad potential benefits for improving local cancer referral practices—especially as there is not just one way to fulfil it, so teams at PCNs and practices have the flexibility to work together to agree the most relevant and beneficial focus for them.

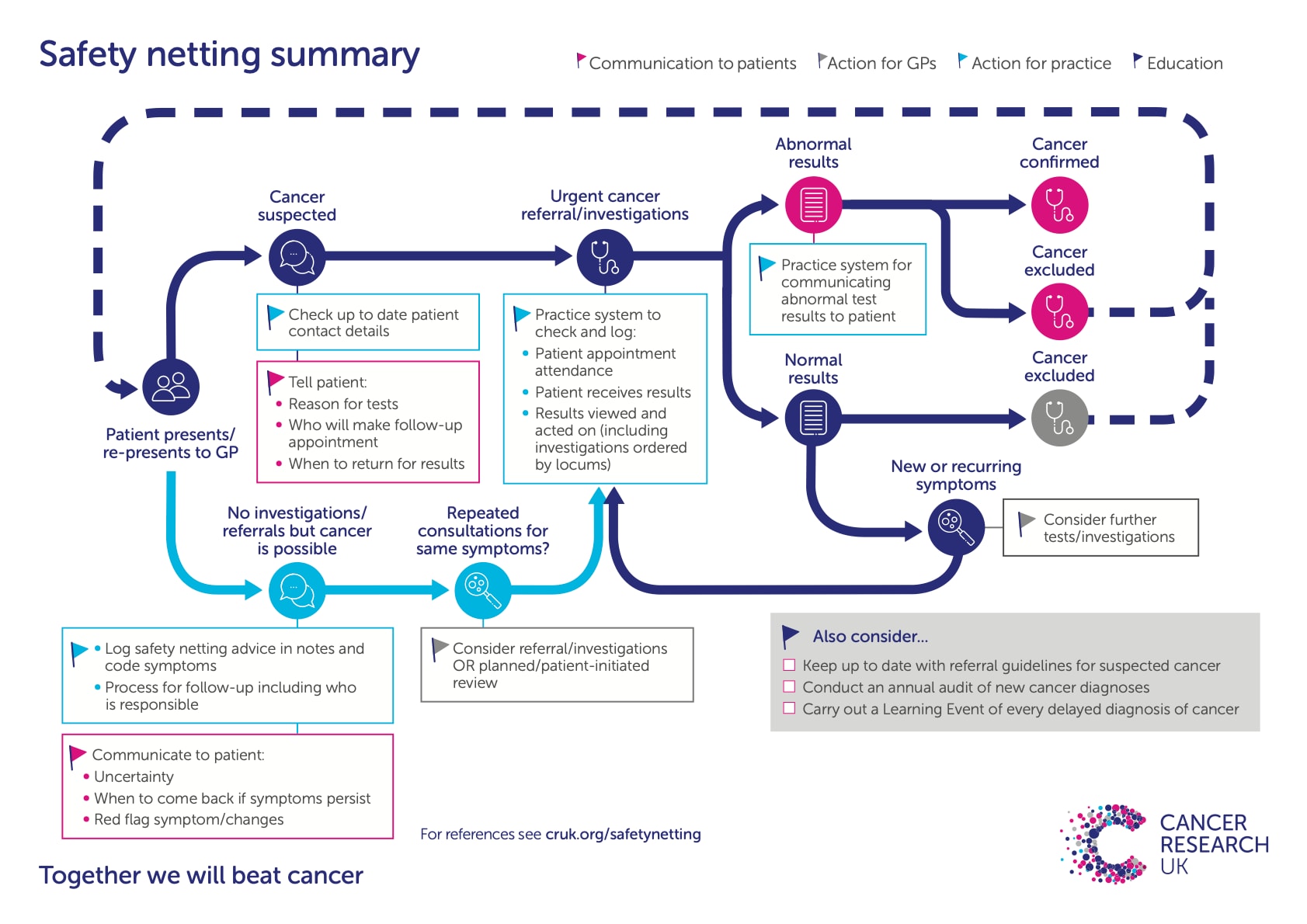

Safety Netting

Perhaps one of the most important processes for practices and PCNs to review and improve is their safety-netting system: uncertainty is an unavoidable constituent of work in primary care, and safety netting is an essential way to combat this. The importance of safety netting is most obvious when considering a potential cancer diagnosis, ensuring that no one ‘falls through the net’ as a result of insufficient information or follow up, whether they are presenting with concerning symptoms, being sent for investigations, or on an urgent pathway.53,54 Primary care can more effectively prevent uncertainty and missed follow up if it uses the right processes, with a clear understanding across the whole team, at all stages of the cancer pathway, including for:

- monitoring people with low-risk symptoms

- following people up after primary-care-led investigations

- providing appropriate patient information (ideally including written information, bearing in mind an individual’s needs)

- reviewing outcomes of urgent referrals.

Figure 2: Safety Netting Algorithm55

For cancer safety netting to be robust, it cannot be considered the sole responsibility of an individual, but is ideally a system-level process with clear roles and responsibilities, underpinned by effective administration, record keeping, and computer systems.53,54,56 Computer-based decision support tools are particularly important in this regard, and there are various tools that provide an effective safety-netting mechanism for patients who are referred on a suspected cancer pathway, or for whom cancer investigations are initiated in the community (for example, a quantitative FIT, PSA test, or cancer antigen 125 test), such as the Macmillan Cancer Support (MCS) electronic safety netting toolkit.57

In practice, local clinical and nonclinical champions can help to drive improvements relating to safety netting. MCS53 and CRUK54 provide resources intended to support the establishment of these systems, and further resources are listed in the PCN DES Early cancer diagnosis support pack.46 These resources are worth reflecting on when reviewing and enhancing any safety-netting processes currently in place.

Learning Event Analysis

Another useful way to review referral practice, which complements safety-netting improvements and involves a process familiar to primary care practitioners, is learning event analysis (LEA), in which specific cases are analysed to identify areas for improvement.46,58,59 The Royal College of General Practitioners considers that ‘learning events’ differ from ‘significant events’ in that they do not reach the General Medical Council’s threshold for harm, but still present an opportunity for learning.58 When done well, this method can lead to improvement at multiple levels, from individual and shared learning to development of practice processes and even wider, system-level changes.59

In the authors' experience, LEA reviews are best led by a member of the team directly involved in the case, then the results shared with the rest of the team for the purposes of learning and quality improvement. Some cases will not only lend themselves to educating practitioners, but also have the potential to prompt changes in processes that, where appropriate, could impact multiple care settings.59 Across a PCN, it may be useful to collate a number of LEA reports in order to analyse and identify trends and wider areas for improvement.59 MCS has a toolkit that can support primary care teams to carry out high-quality LEA.59

Other Areas to Consider

There are other ways to improve local referral practices, including by providing information for clinicians on the symptoms of suspected cancer and on the local pathways available for investigation.46 These now include rapid diagnostic centres (see a previous article by Dr Cunliffe on this topic, Achieve faster diagnosis of suspected cancer via rapid diagnostic centres60), which are intended for those lower-risk symptoms that may not meet the criteria for a 2-week-wait referral. A useful start in planning an activity may be to complete the free educational module provided by GatewayC, Improving the quality of your referral.61

PCNs may also wish to reflect on their practices’ detection rates (the proportion of patients diagnosed with cancer who were referred through a 2-week-wait suspected cancer pathway), and tumour-specific conversion rates (the proportion of patients referred to a particular 2-week-wait suspected cancer pathway who receive a cancer diagnosis).46 The patient interval to primary care and the referral interval into secondary care are other metrics to take into account. By considering important measures such as these, primary care teams can identify potential issues and adapt local interventions to improve the pathway to early diagnosis of cancer.

Summary

As highlighted in this article, primary care involvement is integral for achieving the ambitious national targets for the early diagnosis of cancer. Capacity can be a challenge, especially at a time when primary care is delivering record numbers of appointments,62 so it is particularly important to engage the whole practice and PCN team, utilise computer systems effectively, and focus on the elements of the PCN DES that can have the biggest impact for local populations. This will ensure that any activity has the greatest benefit possible.

| Key Points |

|---|

|

| Implementation Actions for Clinical Pharmacists in General Practice |

|---|

Written by Anthony Shoukry, Clinical Services Pharmacist at Soar Beyond Ltd The following implementation actions are designed to support clinical pharmacists in general practice with implementing guidance at a practice level. As outlined by Dr Cunliffe and Dr Gill, primary care has a vital role to play in improving early cancer diagnosis. The role of clinical pharmacists in general practice continues to evolve, and as such they are often the first healthcare professionals that patients encounter. This puts clinical pharmacists in a unique position to help identify potential cancer symptoms and ensure that patients receive timely and appropriate referrals for further investigation. To help practice-based pharmacists with this task, here are some suggested implementation actions to improve cancer diagnosis and referral. Patient Engagement

For more information on updates within the PCN DES, or for support with QI projects, visit the i2i Network. The i2i Network provides clinical pharmacists in general practice with a suite of training and implementation resources that is FREE and covers a range of long-term conditions. Become a free member at www.i2ipharmacists.co.uk, and find out more about our services atwww.soarbeyond.co.uk. [A] Cancer Research UK. Safety netting summary. London: Cancer Research UK, 2020. Available at:www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/cancer-stats/safety_netting_flow_chart_march_2020/safety_netting_flow_chart_march_2020.pdf [B] NHS England. Network Contract Directed Enhanced Service—Investment and Impact Fund 2023/24: guidance. London: NHS England, 2023. Available at: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/PRN00157-ncdes-investment-and-impact-fund-2023-24-guidance.pdf PCN=Primary Care Network; DES=Directed Enhanced Service; QI=quality improvement; IIF=Investment and Impact Fund; GI=gastrointestinal; FIT=faecal immunochemical test |