Dr Toni Hazell Explains the Role of This Diagnostic Test in the Risk Stratification of People With Symptoms Suggestive of Colorectal Cancer

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

|

In the UK, there are approximately 42,900 new cases of bowel cancer each year, and around 54% of these are preventable.1 Primary care practitioners play an important role in the diagnosis of colorectal cancers, a role that is expanding as a result of NHS initiatives to increase testing in primary care before referral.

This article provides eight top tips on investigating colorectal cancer in general practice, with a focus on using faecal immunochemical testing (FIT) to investigate symptomatic patients.

1. Recognise that Colorectal Cancer Is Rarely Identified Early

Early diagnosis of cancer is inextricably linked to better outcomes. Colorectal cancer is more likely to be curable if identified at an early stage,2 and the survival rate drops sharply with increased stage at diagnosis (see Table 1).2–5

Table 1: Stages of Colorectal Cancer, with Survival Rates3,4

| Stage at Diagnosis | Definition3 | 5-Year Survival4 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tumour in the inner layer of the bowel | 90% |

| 2 | Tumour in the muscle of the bowel wall | 85% |

| 3 | Tumour in the outer lining of the bowel wall | 65% |

| 4 | Tumour outside the bowel wall | 10% |

2. Understand the Key Reasons Why Diagnoses Are Delayed

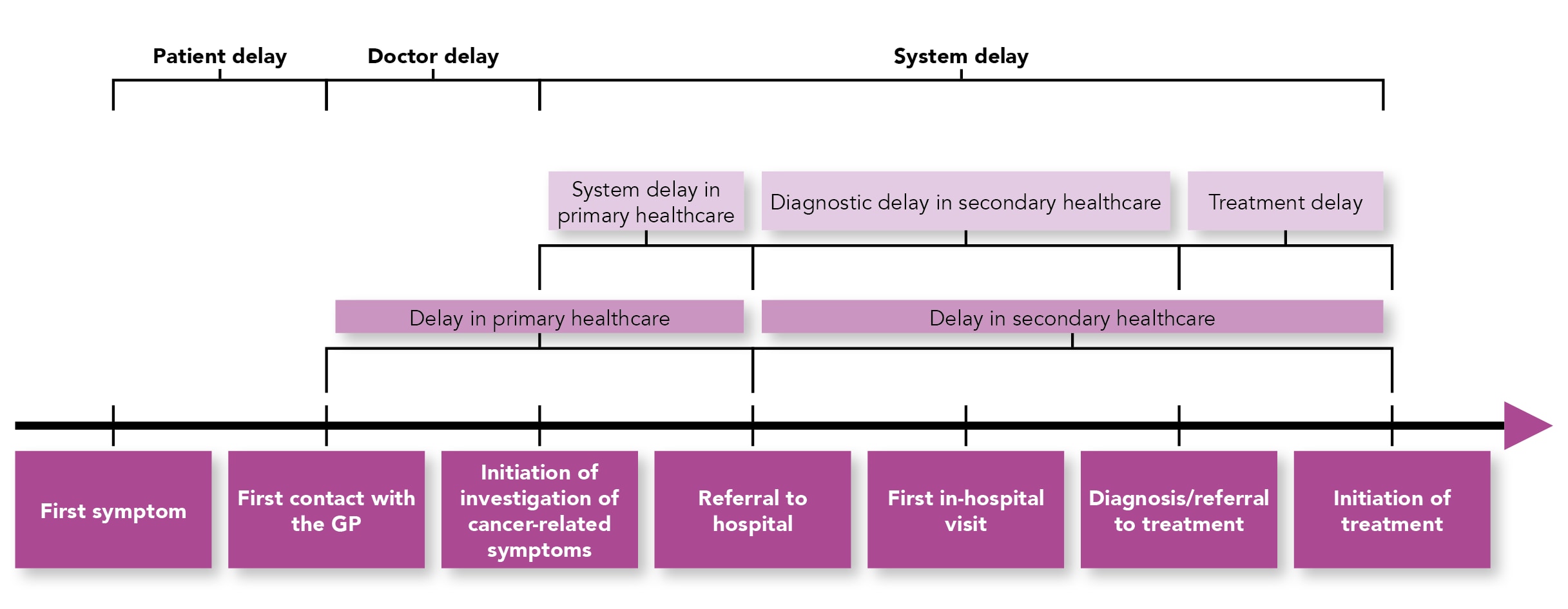

Increasing early cancer diagnosis is not entirely within the remit of general practice. The reasons for delay can broadly be divided into patient factors, clinician factors, and healthcare system factors (see Figure 1).8

Figure 1: Delays in Cancer Diagnosis8

Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. This figure has been reproduced in house style, but otherwise remains unchanged.

Patient Factors

One key patient factor is the tendency of patients to delay seeking help, possibly because they attribute symptoms to other causes or because of false reassurance from a negative screening test (see Tip 6).8

Demographic factors are also important. People with ethnic minority backgrounds and/or who live in areas of socioeconomic deprivation have poorer outcomes for some cancers.5,9,10 This tendency is likely to be multifactorial, and contributing factors in certain minority ethnic groups may include:5,8–10

- reduced uptake of screening

- a delay in seeking help when symptoms present (or people in these groups being less likely to fully disclose symptoms in a first consultation)

- difficulty in accessing healthcare as a result of language issues

- cultural beliefs about cancer being incurable.

Clinician Factors

Clinician factors include the accuracy of the initial diagnosis, the choice of tests, the interpretation of test results, and the choice of pathway for referral.8 With the recent replacement of the (often unmet) 2-week guarantee for a first outpatient appointment after a suspected cancer pathway referral,12 it may now be the case that pathways for lower-risk patients (some of whom will still have cancer) vary more by area; this is a situation that may cause confusion among clinicians and increase the impact of clinician factors on cancer diagnosis. Direct access to diagnostic tests is also relatively new in many places, and varies significantly by area in the UK.13

System Factors

Anyone working in the NHS will be familiar with the key system factors, particularly those concerning delays in diagnosis and referral—waiting lists have risen relentlessly over the last 10 years, with a steeper increase over the COVID-19 pandemic.14 An individual, full-time-equivalent GP is now responsible for 2,299 patients, an increase of 19% since 2015, and 1,996 fewer full-time equivalent GPs were working in the NHS in October 2023 compared with in September 2015.15 It makes sense that a system under ever-increasing pressure will leave patients at risk of later diagnosis and poorer outcomes.

3. Navigate the Referral Criteria for Suspected Colorectal Cancer

The NICE guideline on suspected cancer16 was considered groundbreaking when it was introduced in 2005.17 For the first time, a list of worrying symptoms was given for every bodily system;17 the criteria were based on different symptoms and prevalences of cancer in each system, but the symptoms listed as warranting investigation would generally indicate a positive predictive value (PPV) of 5% or more.18 The current iteration of this guidance uses a lower PPV of 3% to underpin the recommendations, with an undefined value of ‘significantly below’ 3% for cancers in children and young people.18

In some areas, the recommendations are very simple—for example, the recommendation for investigating cancer of the cervix simply says to ‘consider a suspected cancer pathway referral for women if, on examination, the appearance of their cervix is consistent with cervical cancer’.16 The colorectal cancer section, updated in August 2023, is much more complex (see Box 1); the symptoms that should trigger a suspected cancer referral have always varied with age, but NICE now includes an extra variable in requiring the use of FIT before referral for all except those with a rectal mass, anal mass, or unexplained anal ulceration.16 This advice is mirrored in recent diagnostics guidance about FIT.16,19

| Box 1: NICE’s Referral Criteria for Colorectal Cancer16 |

|---|

© NICE 2023. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. NICE Guideline 12. NICE, 2015 (updated October 2023). Available at: www.nice.org.uk/ng12 |

4. Know the Benefits of FIT Versus Faecal Occult Blood Tests

Clinicians who learned about the faecal occult blood (FOB) test in medical school may be confused about the emphasis being placed on FIT. The standard FOB test is a qualitative test that gives a yes or no answer as to the presence of blood in the stool. It requires dietary and medication restrictions, as false-positive tests can occur after the patient eats certain foods (such as oranges, bananas, horseradish, or artichokes), if the patient is taking certain medications (such as aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), or because of excessive alcohol consumption.20

In contrast, FIT quantifies the amount of human haemoglobin present in the stool, allowing for different thresholds for a positive result in different populations, and is reliable regardless of diet and medication.19,20 FIT also has a higher sensitivity and specificity than the FOB test, with a sensitivity of over 87% for symptomatic patients (when applying a cutoff of 10 mcg/g of faecal haemoglobin [fHb]), increasing to 90% for those with rectal bleeding.21 This is why FIT has now become the preferred investigation.

5. Reassure Patients Who Have Negative FIT Results …

The NHS is a resource-pressurised system—every patient who is referred causes an increased delay for those behind them in the queue. Therefore, any test that can accurately stratify risk is useful, as it can lead to referrals that are more accurately targeted. A patient who has symptoms that would have previously required referral under the suspected cancer pathway (formerly known as a 2-week-wait referral), but who has a FIT result below 10 mcg/g, has the same risk of colorectal cancer as someone who has no relevant symptoms.21 This risk is approximately the same as that of having severe complications from a colonoscopy.21

This should reassure both patients and clinicians that the balance of risks and benefits favours no suspected cancer pathway referral, freeing up that pathway for those at higher risk. However, low risk does not equate to no risk, and there may be an alternative pathway that is relevant for this cohort. GPs should not ignore their gut feeling when concerned about a patient (see Tip 7).

6. … But Appreciate the Difference Between FIT Results from Symptomatic Testing and from Testing Undertaken by the Bowel Cancer Screening Programme

Importantly, FIT done as part of the national bowel cancer screening programme (that is, for an asymptomatic patient) has a very different threshold for positivity to FIT for symptomatic patients.19,22 This relates to issues of sensitivity and specificity, and the effect that a test’s threshold has on them.

Determining Thresholds: Sensitivity Versus Specificity

No test is 100% accurate, and there will always be false positives and negatives. The sensitivity of a test is how likely it is to identify someone with the disease—a highly sensitive test will have few false negatives, but may have many false positives.23,24 The specificity of a test is how likely it is that someone without the disease will get a negative result—a highly specific test will return a positive result for very few people who do not have the disease, but it may miss some who do.23,24 Specificity is therefore the opposite of sensitivity. Altering the threshold at which a test is considered positive inversely changes the sensitivity and specificity of the test, and a balance must be found between the two—as sensitivity increases, specificity decreases, and vice versa.23

FIT for someone with symptoms suggestive of colorectal cancer is considered positive at a threshold of 10 mcg/g or more in most cases, and this should prompt a suspected cancer pathway referral.16,19,21 However, when guidance in this area was being written, a variety of thresholds were considered.19,21 For the 10 mcg/g threshold, there is likely to be only one missed cancer per 1000 patients, and approximately 10 people need to undergo further investigations to detect one cancer.21,25 A lower threshold of 2 mcg/g would have reduced the number of missed cancers to four per 100,000 patients (0.04 per 1000 patients), thus increasing the sensitivity.21,25 However, using this threshold would also have doubled the number of people being investigated per cancer found to 21, thus decreasing the specificity, increasing the risk of complications, and not allocating resources as efficiently as with the 10 mcg/g threshold.21,25

Exact thresholds will vary between regions and laboratories, so it is always worth looking carefully at the result provided. In Northern Ireland, for example, the positive threshold for symptomatic FIT is 7 mcg/g.22

Differences Between Screening and Symptomatic FIT Thresholds

In order to have a positive result from the national screening programme, a patient in England or Wales must have an fHb of 120 mcg/g or greater,26,27 with a slightly lower threshold of 80 mcg/g applying in Scotland28 and a higher threshold of 150 mcg/g applying in Northern Ireland.29 These thresholds, far higher than for symptomatic patients, will have been chosen with resources in mind—increasing the threshold reduces the number of investigations per cancer found but increases the number of cancers missed, making the test more specific; reducing the threshold instead reduces the number of false negatives but increases the number of investigations per cancer found, making it more sensitive.

Impact on Practice

A patient with symptoms may, in trying to be helpful, tell their GP that they do not need FIT because they have recently had a negative test through the screening programme. However, because of these different thresholds, it can easily be the case that a patient would simultaneously return a negative screening FIT and a positive symptomatic FIT. Therefore, the test should always be done, even in the presence of a recent negative screen.16,19,21

7. Do Not Ignore Your Gut Feeling

FIT is not 100% accurate at identifying colorectal cancers, and GP intuition (or ‘gut feeling’) is actually known to be a valuable diagnostic tool when it comes to cancer diagnosis.30–32 The occasional patient with symptoms of colorectal cancer and a FIT result below 10 mcg/g will still have colorectal cancer, and some will have other diagnoses that account for their symptoms. It is important that GPs are still able to refer patients if they have concerns, particularly if symptoms persist,21 and some areas have therefore developed FIT-negative pathways to which patients can be referred if they have a FIT result below 10 mcg/g but still have symptoms that would previously have merited a 2-week-wait referral for colorectal cancer.

One example of such a pathway is in North Central London, where symptomatic patients with a FIT result below 10 mcg/g are given a repeat full blood count, a repeat FIT, and a virtual follow-up appointment within 8–10 weeks, followed by review with a consultant or senior registrar.33 Options at this point include discharge back to the GP, upgrade on to the urgent cancer pathway, and further investigations on the routine referral-to-treatment pathway.33 In the absence of such a pathway, a GP may choose to refer to Gastroenterology or a colorectal surgeon, explaining what the ongoing concern is, or use an Advice and Guidance service to discuss the patient and work out what the most appropriate pathway would be.

8. Ensure That Your Practice Has Good Safety-Netting in Place

The introduction of FIT into the colorectal cancer pathway is one of the few areas in which a diagnostic test is mandatory before a referral is made. For most other symptom-based areas in the suspected cancer guideline, the referral is made based on symptoms or signs, and should be done within 24 hours of the patient being seen.16

Adding a test in primary care does increase the risk that a patient will be missed, such as if they fail to return the test or the result is lost in the system, making it particularly important that practices have robust safety-netting procedures in place. These procedures may include having one member of staff who is in charge of this area of practice (with cover for holidays or other absences), with all FIT requests being reported to that person. This person could proactively follow up patients if their sample has not been returned within a few days, or if no result has come back when a sample has been sent to the laboratory.

Technology can be used to assist such initiatives, with most GP software systems having safety-netting templates and the ability to run searches based on the dates entered into them.33 However, a system is only as strong as its weakest (usually human) link, so it is important that every clinician knows about the practice’s system for FIT and onward referrals, and that patients are empowered to return if their symptoms persist or worsen, or if new red-flag symptoms occur, even if a referral was not considered necessary at their first assessment.16,33,34

Summary

The use of FIT has changed the criteria that clinicians use to suspect colorectal cancer, hopefully allowing limited resources to be used more efficiently. GPs should understand why FIT is being used and be able to explain this to patients with symptoms, reassuring them that their risk of cancer is very low if their FIT result is below 10 mcg/g. That said, clinicians should still value their clinical instincts, and refer down an appropriate pathway if they have concerns.