Medscape asked top experts to weigh in on the most pressing scientific questions about COVID-19. Check back frequently for more COVID-19 Data Dives, and visit Medscape's Coronavirus Resource Center for complete coverage.

Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, BSc, MPH

Recently, a new preprint from John Ioannidis was posted online. Ioannidis famously authored the 2005 paper titled "Why Most Published Research Findings Are False." This new one already has an Altmetric score of 541, so it's getting a lot of buzz.

Here's my peer review.

The study's aim was to estimate the infection fatality rate (IFR) of COVID-19 using seroprevalence (antibody test) studies. The analysis included population studies with a sample size of at least 500, which had been published as peer-reviewed papers or preprints as of May 12, 2020. Studies on blood donors were included, but studies on healthcare workers were excluded.

At first glance, this methodology is not ideal.

The issue is that if you want to estimate a number like this from published data, you want your search and appraisal methods to be systematic—hence, systematic review.

Instead, what we appear to have here is an opaque search methodology and little information on how inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied (with no real justification for those criteria).

For example, seroprevalence studies including healthcare workers were excluded because the samples are biased. But studies of blood donors were included, even though these are arguably even more biased. That's a strange inconsistency.

Studies only described in the media were excluded, but this appears to have included government reports as well. Again, there's no justification for this and it is really weird to exclude government reports. (They're doing most of the testing!)

The analysis then calculated an inferred IFR for each study if the authors hadn't already done so. The calculation is crude but not entirely wrong. However, the estimates were then "adjusted." And this is a problem.

Specifically, the IFR estimates were cut by 10%-20% depending on whether they included different antibody tests or not. The rationale for this decision as described in the article doesn't support such a blanket judgement.

So, on to the results. The crux of the review is a table documenting prevalence and IFRs of the 12 studies included. "Corrected" IFRs ranged from 0.02% to 0.4%—much lower than most published estimates.

A colleague and I did a systematic review and meta-analysis of published estimates of COVID-19 IFR and came to an aggregated estimate of 0.64% (0.5%-0.78%). So their lower result is a bit of a surprise to me.

Looking at the data included in this paper, some factors immediately spring out that could have contributed to our very different results.

First, three of the studies included in this new analysis were conducted in a population of blood donors (Denmark, the Netherlands, Scotland).

It is easy to see why blood donor studies aren't actually estimates of IFR. Blood donors are, by definition, healthy, young, etc. So any IFR calculated from these populations is going to be much lower than the true figure.

This problem is repeated when we look at other studies included in the analysis. Studies conducted in France and Japan both used highly selected patient populations, both of which likely would lead to a biased (low) estimate of IFR. (The same concern has been raised about the Santa Clara study, but for now let's ignore that and move on.)

(Editor's note: Ioannidis has addressed concerns raised about the study conducted in Santa Clara in a recent interview.)

Remember when I said that the calculation of individual IFRs was reasonable? When Ioannidis calculated IFRs, he did a decent job, but some of the included studies weren't as meticulous.

For example, the Iran, Japan, and Brazil studies made no attempt to account for right-censoring. The basic idea of right-censoring is simple: If someone leaves a study before their event happens, it's not counted and therefore the study's results are skewed. That's an issue.

In addition, the Iranian study uses the official figure for deaths. It has been pointed out that this number may be a significant underestimate.

So, several studies are clearly not estimates of population IFR. They look at specific, selected individuals and can't be extrapolated. And others (Iran and Brazil) are probably underestimates due to methodology.

If we exclude these potentially misleading numbers, the lowest IFR estimate immediately jumps from 0.04% to 0.18%. Coincidentally, that 0.18% is Ioannidis' own research: the Santa Clara study.

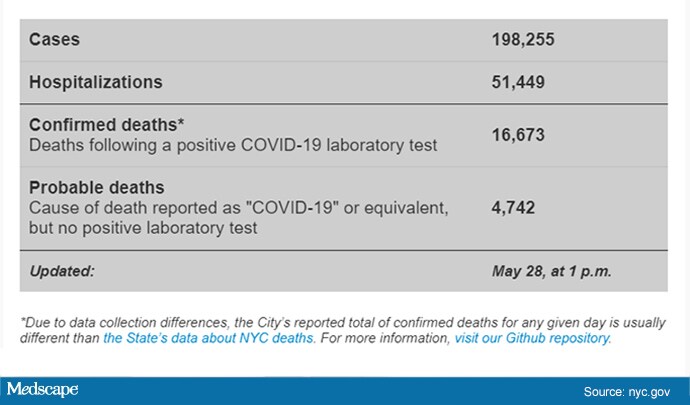

To me, a low estimate of 0.18% makes much more sense than a minimum IFR of 0.02%. Why? Well, take New York City. Approximately, 16,000 deaths in a city of 8.4 million means that if every single person has been infected, the IFR would be 0.19%. (The Figure presents current information for COVID-19 disease in New York City at the time of this writing.)

Figure. COVID-19 case information in New York City.

Everyone calls New York City an outlier, and perhaps it is. But if you repeat this calculation for other places in the United States, the same chilling thing happens:

Massachusetts: 0.9%

New Jersey: 0.12%

Connecticut: 0.1%

The same is true of other places overseas. Lombardy has a total death toll of 0.16%. Madrid is around the same; even London is above 0.1% dead due to COVID-19. It seems incredibly unlikely, at this point, for the IFR to be below 0.1%.

Now, this is noted in the preprint article but appears, to my interpretation, to be dismissed as the deaths of old and poor people.

In particular, Ioannidis argues that places with lots of elderly and disadvantaged individuals are "very uncommon in the global landscape." This is trivially incorrect. Most of the world is far worse off than people in New York City.

There's also some discussion of the obviously underestimated studies, pointing out that they may not be representative of the general population.

So why were they included in the first place if they are clearly not realistic numbers?

Alternatively, why wasn't a Spanish seroprevalence study included? It is the biggest in the world and estimates IFR to be approximately 1.0%-1.3%. This is triple the highest estimate in this review! Meanwhile, clearly biased estimates were included?

I'm also interested to know why 500 was arbitrarily the minimum size considered for included research. If the minimum is increased to 1000, the IFRs are suddenly much higher.

And that brings me to the conclusion in this paper, which, frankly, is a bit astonishing:

Is it a fact? That's certainly not shown in this review. Most evidence seems to directly contradict this statement. The final thoughts included in the preprint may make the author's conclusions a bit more understandable. It seems the author is not a fan of lockdowns, stating that the findings in his analysis may inform a more tailored approach and avoid "blind lockdown of the entire society." Perhaps this has driven his decisions for his review?

Ultimately, it's hard to know the why, but what we can say is that this review appears to have very significantly underestimated the IFR of COVID-19. Moreover, the methodology is quite clearly inadequate to estimate the IFR of COVID-19, and therefore the study fails to achieve its own primary objective.

Another weakness of this study, pointed out by others, is that the author appears to have taken the lowest possible IFR estimate from each study. For example, the authors of a study conducted in a small community in Germany posited an IFR of 0.37%-0.46%. The Ioannidis analysis cites 0.28%. The rationale for correcting the German researchers' calculation was that the cases in that city were the result of a superspreader event (a local carnival), and seven deaths were recorded in the city, all of them in very elderly individuals

Another good critique of the study points out a similar problem with citation of the data from the Netherlands study. The number provided in this review is roughly six times lower than the true IFR.

Because this paper is currently a preprint, there's a great opportunity to correct the record in real time and put up a study that actually achieves its aims.

Let's hope it happens.

Of course, I personally wish that the IFR of COVID-19 really was 0.02%. It would solve so many of our problems. Unfortunately, it seems extremely unlikely.

Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz is an epidemiologist and doctoral candidate at the University of Wollongong. His expertise is in chronic disease, epidemiology, and burden of disease. He is widely published, with articles appearing in The Guardian, New York Observer, New Daily, Inside Story, and elsewhere. Visit his blog and follow him on Twitter

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Medscape Internal Medicine © 2020 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: COVID-19 Data Dives: Why I Think Fatality Rates Are Higher Than the Estimates - Medscape - Jun 03, 2020.

Comments