For the first time in the UK, several babies have been born who technically have DNA from three people as a result of a procedure called mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT). Results of the effort, from a team at Newcastle Fertility Centre, are expected to be published soon.

The UK body that oversees decisions on fertility treatments, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), confirmed the births earlier this year, after a freedom of information request from The Guardian newspaper.

Dubbed 'three-parent babies' by the press, these children do have genetic material from three people — their biological parents, plus mitochondrial DNA from a female donor. However, researchers stress that the amount of DNA from the donor is tiny; these infants still have more than 99% of their DNA from their two biological parents.

Every time new births using MRT are announced, headlines are often generated worldwide, beginning with a primitive version of the process more than 25 years ago. But what is the science behind the procedure, when and why has it been used, and should the rules be changed, especially in the UK?

How MRT Works

Mitochondrial replacement therapy has been attempted previously for two different aims: (1) to help couples in whom the female carries a rare mitochondrial disease, or (2) for idiopathic infertility and repeated in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) failures (sometimes also called "age-related" infertility).

The Newcastle team used MRT to help parents in whom there is an inherited mitochondrial disease. Mitochondrial DNA is solely inherited from the mother through the egg (mitochondria from sperm are eliminated after fertilisation).

Use of the technology is permitted in the UK only for mitochondrial disease, not for infertility.

Mitochondrial diseases are caused by an inability to produce enough energy for cells or organs to function properly. Symptoms include poor growth, loss of muscle coordination, vision and hearing problems, autism, diabetes, and neuropsychological symptoms.

It's not known whether women with mitochondrial disease struggle to get pregnant. But these women have often lost multiple pregnancies and/or already gave birth to affected offspring, most of whom live with terrible symptoms and die prematurely in childhood or adolescence.

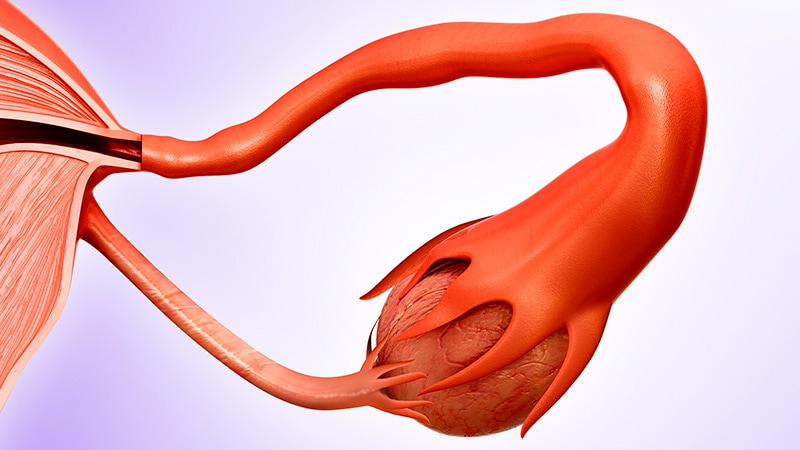

MRT — sometimes called mitochondrial donation — is performed either just before or after fertilisation. The nuclear material from the mother's egg (or from an embryo created from the mother's egg and the father's sperm) is transferred into a donor egg (or into an embryo created from a donor egg and a sperm) that has had its own nuclear material removed.

This nuclear DNA transfer seeks to ensure that the offspring's nuclear DNA replicates in cells with functional mitochondria.

At least three different ways are used to do this, including:

- Maternal spindle transfer (MST). Moving DNA before the mother's egg is fertilised. The 'spindle' from the mother's egg is removed and placed into an enucleated donor egg – so that the latter now contains nuclear material from the mother and mitochondria from the donor. The egg is then fertilised using the father's sperm. If a viable embryo results, it's considered for transfer to the mother's womb.

- Pronuclear transfer. Moving DNA after formation of the embryo. This method isolates the pronuclei (the nuclear material after fertilisation of the maternal egg by the father's sperm) from an embryo and transfers it into an enucleated donor embryo (donor egg fertilised by sperm). The resulting embryo now contains nuclear material from the mother and father, and mitochondria from the donor egg. If viable, the embryo will be considered for transfer to the mother's womb.

- Polar body transfer. This is a relatively new technique, which isolates one of the two polar bodies of the meiotically dividing cell — that will ultimately become the embryo formed from the mother's egg and father's sperm — and which would otherwise be ejected as "spare" nuclear material, and transfers it into an enucleated embryo (zygote) with normal mitochondria. Polar body transfer has the advantage of having a lower risk of carrying over maternal mitochondria (see below) and already has a proven track record in mice. However, it is currently not permitted in the UK.

Both (a) and (b) eliminate most of the faulty mitochondria but risk carrying over a small number of mutant mitochondria from the mother's cytoplasm to the donor egg or embryo (zygote).

And although nuclear material is moved during both MST and pronuclear transfer, this material is not contained within a single nucleus. This is because the single nucleus that would ordinarily be present in a cell is temporarily absent during these particular stages of reproduction. Instead, the material that is moved during these techniques consists of two pronuclei (in the case of pronuclear transfer) or one maternal spindle (in the case of MST).

The Newcastle team are believed to have used the pronuclear transfer technique.

Recent MRT Procedures Used for Infertility

A few babies conceived using MRT have previously been born in a clinic in Ukraine, where the women were selected because they had repeatedly gone through IVF but failed to conceive, Robin Lovell-Badge, FRS, FMedSci, of the Francis Crick Institute in London, told reporters at a recent UK Science Media Centre press briefing. But, "we have no idea of the outcomes, as there have been no [scientific] publications, although some [results] were presented at medical meetings," he noted. Because of the war in Ukraine, further follow-up of these patients seems unlikely at the moment.

"And to be fair to the Ukrainians, they never said [the technology] was 'mitochondrial', they said it was 'cytoplasmic'," observed Andy Greenfield of Nuffield Department of Women's & Reproductive Health at the University of Oxford.

Separately, the birth of six babies using MRT was reported earlier this year by a Spanish/Greek team — and crucially this time the research was published — again for the purpose of treating unexplained infertility. These couples had undergone, on average, a mean of 6.4 cycles of IVF per couple without any resulting pregnancies before they tried MRT.

After the procedure, all six successful pregnancies were delivered by caesarean at 38 weeks, with the newborn and placenta weights within normal ranges. Nuno Costa-Borges of Embryotools, Parc Cientific de Barcelona, Spain, and colleagues reported these findings from their pilot study in Fertility and Sterility, published online in February. Paediatric follow-up of the children, performed at intervals from birth to 12-24 months of age, has not revealed any clinical abnormalities.

"This Greek/Spanish publication got a lot of attention, [because they had] remarkable results," Greenfield told the London media briefing.

Following any children born from this technology is key, because it is not known how inheriting even a miniscule amount of DNA from a third person will affect any resulting child over the course of its lifetime, the experts stressed.

"The responsible people will be telling you how the kids are doing. Not just [saying], 'We made a baby'," noted Peter Braude, professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at Kings College, London. "It's a travesty if you don't follow them up," he added.

"You are creating 'heteroplasmic' children," explained Professor Braude. "It's extraordinarily complicated, a real uphill learning experience."

Tens of Children in the US Born Previously with Primitive Technique

Prior to this recent publication by Costa-Borges et al, there are thought to have been around 20-30 children born in the US between 1996 and 2001, in whom there was some introduction of mitochondria from donors into the mother's eggs, using a somewhat primitive technique. News of their conception — they were dubbed genetically modified (GM) babies — created headlines around the world.

But little, if any, proper follow-up was performed on these children.

Also, in 2003, a woman in Guangzhou, China, became pregnant after doctors there used donor eggs but replaced the nuclei of the donor eggs with those of the mother, prior to IVF.

Three resulting embryos were implanted in the mother, but the triplet pregnancy was reduced to a twin one to reduce risk. The two remaining foetuses survived to 24 and 29 weeks, and then aborted prematurely. An abstract describing this procedure was presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine conference in October 2003 and published in Reproductive Biology in 2016. Once the case hit the headlines in China, the government stepped in and stopped the work.

Likewise, when the procedures performed in the United States made news there, in 2001, the FDA subsequently informed IVF clinics in 2002 that using a third person's cytoplasm, and the mitochondria contained therein, would require an investigational new drug application (IND), the same as is required for new pharmaceuticals.

This was because it was effectively a new and untested treatment, the FDA said. This made any further attempts financially unviable, and the procedure was abandoned in the United States.

However, this didn't stop John Zhang — who led the research group that enabled the pregnancy in Guangzhou, China, but who subsequently moved to a fertility clinic in New York — from attempting this process again, in 2016.

His team circumvented US law by treating the woman at a private IVF clinic in Mexico. According to The Guardian, the mother was a Jordanian woman who carried two mitochondrial mutations which cause a fatal condition called Leigh syndrome. Prior to the treatment, the woman had had four miscarriages and two children – one died aged 6 and the other lived for only 8 months.

"It's not so much [the fact] that he [Zhang] did it in another country, it was the way it was done to avoid the regulations in the US," Lovell-Badge told Nature in 2017.

MRT for Mitochondrial Disease Only, or Use for Infertility?

In scientific circles, researchers seem to be split between those who believe that trying to develop MRT for infertility is just a money-making exercise, versus those who think this might well turn out to be a viable option for "older" eggs that can be rejuvenated with mitochondrial material from a younger donor egg.

Few scientists, however, would argue against its use for mitochondrial disease, so devastating are these conditions, although they are also extremely rare.

An editorial accompanying the publication in Fertility and Sterility applauds their work, but the authors stress that the Spanish/Greek researchers were keen to "emphasise the preliminary nature of their study and that controlled randomised clinical trials are needed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the techniques before their wider clinical application".

What About Mitochondrial Reversion?

Also of some concern was that while genetic sequencing determined that five of the six children in the Spanish/Greek study got more than 99% of their mitochondrial DNA from the donor (the intended effect, to circumvent potentially defective maternal mitochondrial DNA), in one case, the child had 30% to 60% maternal mitochondrial DNA.

While the latter may not be a huge issue for infertility, it obviously is much more of a concern when this technology is being used to treat maternally inherited mitochondrial disorders.

A tiny quantity of the mother's mitochondria is likely to be carried over with the nuclear material, however. Scientists are looking for ways to reduce this "carryover" as much as possible, but they may not be able to eliminate it completely.

And very rarely — no one yet really understands why currently — these small amounts of maternal mitochondria subsequently outcompete healthy mitochondria from the donor in a process termed "mitochondrial reversion".

It isn't known either how this "carryover" of maternal mitochondria might differ among the different techniques of MRT: MST, pronuclear transfer, and polar body transfer.

But as Lovell-Badge said, "Once you go from the lab to the clinic, things get messy." When the Newcastle team publishes their findings with pronuclear transfer, he hopes to have some clarity on the carryover effects.