Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape's Coronavirus Resource Center.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I'm Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

In the coronavirus era, pregnant women represent a unique cohort in the hospital. They can have florid COVID-19 symptoms, and deaths have been reported. Of course, they may also be in the hospital just to deliver a baby and have COVID detected incidentally.

Early on in the pandemic, a friend of mine — an anesthesiologist in New York City — told me how overwhelmed he was with COVID cases. Not in the ICU; he was working in the maternity ward. Ordinary pregnancies became complicated, C-sections spiked, and outcomes worsened. But until I saw this paper appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine, his experience was just another anecdote in a sea of COVID war stories.

Finally, we have some hard data on the risks of COVID-19 in pregnancy. And we need it now more than ever, as women who are pregnant or are thinking of becoming pregnant will need to make decisions about getting a vaccine — a vaccine that was evaluated in studies specifically excluding pregnant women.

Women who become pregnant tend to be younger and healthier than the general US adult. As such, in the absence of pregnancy, they would often be considered low risk and not a vaccine priority group. But this paper shows that COVID-19 has some pretty significant effects in pregnancy, and we need to take those risks into account when we consider whether to advise vaccination.

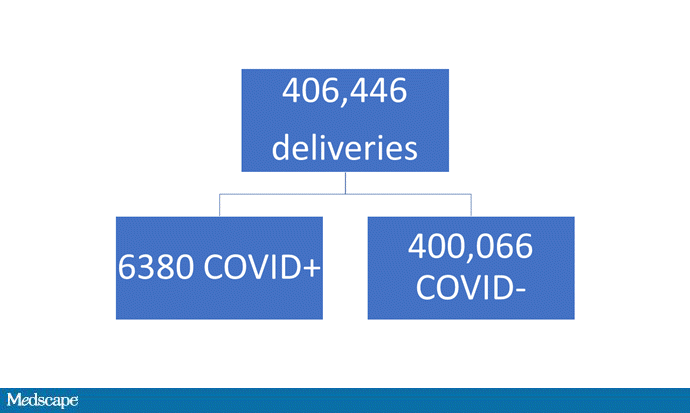

The study leveraged an absolutely huge database that combines records from multiple payers to capture 20% of all deliveries in the US between April 1 and November 23, 2020 — 406,446 women total, of whom 6380 (1.6%) had COVID at the time of delivery. The authors compared baseline characteristics and outcomes across these two groups.

Women delivering a baby while infected with COVID tended to be younger than those without COVID. Mirroring the national prevalence, they were more likely to be Black or Hispanic, more likely to have diabetes, and more likely to have obesity.

The authors adjusted for those and other factors to determine what the independent effect of COVID-19 was on pregnancy outcomes. Now, bad things happening during pregnancy is pretty rare in this country, so I want to be clear that I am presenting relative increases in risk, not absolute risk. For example, COVID was associated with a 25-fold increase in the risk for mechanical ventilation — but just 1.3% of women with COVID were intubated overall.

Women with COVID had a relative 7% increased risk of having a cesarean delivery, a 19% increased risk for preterm labor, and a 23% increased risk for stillbirth. They had a sixfold increased risk of going to the intensive care unit and a 3.5-fold increased risk for venous thromboembolism. Nine women died in the COVID group and only 20 in the 60-fold bigger COVID-negative group.

Again, most women had none of these things, but the presence of COVID clearly increases the risk.

Against that backdrop, what do we know about the risks and benefits of vaccination in pregnant women? Not much. They were excluded from the major clinical trials that led to the current vaccine approvals in the US. Some women did get pregnant during their participation in the Pfizer and Moderna trials — I break down their outcomes here — but the vast majority of outcomes are unknown, presumably because these women are still pregnant. There are no red flags, but obviously not a lot of data to go on.

There's not much reason to think, biologically, that the mRNA vaccines would lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes, but that may not be reassuring to many women. For many women, the vaccine will best balance their assessment of risk and benefit. For others, enhanced vigilance to hand hygiene, mask-wearing, and avoiding crowds may be the best choice to mitigate risk.

One thing is clear: If you can avoid getting COVID while you're pregnant, you probably should.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale's Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and hosts a repository of his communication work at www.methodsman.com.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Medscape © 2021 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: COVID-19 in Pregnancy: Finally, Some Hard Data - Medscape - Jan 20, 2021.

Comments